Narcolepsy

Highlights

Overview

- All people with narcolepsy experience excessive sleepiness during the day. Most also experience sudden but temporary muscle weakness (called cataplexy), usually brought on by strong emotions. Excessive sleepiness during the day may be characterized by the following behaviors:

- Patients typically have periods of drowsiness every 3 or 4 hours that usually end in short naps.

- Patients may sleep for a few minutes during the day, particularly if they are in an awkward position, or for a few hours if they are lying down.

- Patients often underestimate the duration of their drowsy periods and may not recall clearly their behavior during that time.

- Narcolepsy affects about 1 in 2,000 people.

- Narcolepsy is not caused by mental illness or psychological problems, though it is often mistaken for such.

Genetic Basis

- Nearly 98% of patients with narcolepsy test positive on stet cataplexy for specific human leukocyte antigen (HLA) subtypes, particularly HLA-DQB1*0602. This antigen is found in just 20% of the general population.

- Having a family member with narcolepsy presents a 20 - 40 times higher risk of developing the condition compared to the general population.

Causes

- A deficiency in the neurotransmitter hypocretin (orexin) has been implicated in the cases of narcolepsy with cataplexy, the most common form of the condition.

Treatment

- The main drug treatments for narcolepsy are:

- Modafinil (Provigil) for excessive, uncontrollable, daytime sleepiness

- Armodafinil (Nuvigil) for excessive, uncontrollable, daytime sleepiness

- Sodium oxybate (Xyrem) for cataplexy (sudden muscle weakness) for excessive daytime sleepiness. The FDA has placed tight restrictions on the use of this drug. Very serious side effects -- including seizures, coma, and death -- have been reported in people who abused this drug. Trials of Xyrem, however, have not reported these effects with the doses used in treatment for cataplexy.

Introduction

Narcolepsy is considered a primary hypersomnia (excessive sleepiness) condition. Primary means the condition is not caused by another disease. The word narcolepsy comes from two Greek words roughly translated as "seized by numbness." The two primary symptoms in narcolepsy reflect this phrase:

- Excessive daytime sleepiness, with frequent daily sleep attacks or a need to take several naps during the day.

- Temporary and sudden muscle weakness (called cataplexy), usually brought on by strong emotions.

Some patients experience other symptoms:

- Microsleep episodes, in which the patient behaves automatically but without conscious awareness

- A sense of paralysis that occurs between wakefulness and sleep (called atonia)

- Dreamlike states between waking and sleeping (called hypnagogic or hypnopompic hallucinations)

Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep is abnormal in narcolepsy. (REM sleep is the active, dreaming phase of sleep.) In fact, narcolepsy is sometimes defined as the loss of boundaries between wakefulness, non-REM sleep, and REM sleep.

Primary Symptoms of Narcolepsy

Excessive Sleepiness. All people with narcolepsy experience excessive sleepiness during the day with episodes of falling asleep rapidly and inappropriately, even when fully involved in an activity. It is sometime described as an irresistible daytime need for naps, which will generally refresh the patient. These events may be characterized by the following behaviors:

- Patients typically have periods of drowsiness every 3 or 4 hours that usually end in short naps.

- Patients may sleep during the day for a few minutes, particularly if they are in an awkward position or for a few hours if they are lying down.

- Patients often underestimate the duration of their drowsy periods and may not recall clearly their behavior during that time.

Cataplexy. Cataplexy is an abrupt but temporary loss of muscle tone or strength that results in an inability to move and always occurs during wakefulness. Symptoms of excessive daytime sleepiness may be present for years before symptoms of cataplexy develop. About two thirds of patients with narcolepsy have symptoms of cataplexy. The following events may be triggers for cataplexy:

- Sudden emotion, usually anger or laughter (the most common trigger)

- A heavy meal

- Stress

Muscle reflexes are completely absent during a cataplectic attack. Cataplectic attacks can be very minimal and appear as passing weakness or affecting only the eyelids and face. They may, on the other hand, be so severe that they weaken the whole body. In the most severe form of cataplexy, attacks can recur repeatedly for hours or days. Abrupt withdrawal from certain drugs used to treat narcolepsy, notably clomipramine, can trigger these severe symptoms.

Cataplexy may have the following characteristics:

- Most attacks last fewer than 30 seconds and can be missed by even skilled observers. However, in severe cases, a person may fall and remain paralyzed for as long as several minutes.

- Typically the patient's head will suddenly fall forward, the jaw becomes slack, and the knees will buckle.

- Speech may become suddenly loud or broken and stutter-like.

Other Symptoms of Narcolepsy

Atonia. Atonia is a sense of paralysis that occurs between wakefulness and sleep, usually upon waking or sometimes at the onset of sleep. The person is conscious but cannot speak, move (cannot even open their eyes), or breathe deeply. Atonia rarely lasts beyond 20 minutes, but when it first occurs the experience can be terrifying, particularly if the patient also develops hallucinations.

Hypnagogic Hallucinations. Hypnagogic hallucinations are dreams that intrude on wakefulness, which can cause visual, auditory, or touchable sensations. They occur between waking and sleeping, usually at the onset of sleep, and can also occur about 30 seconds after a cataplectic attack.

- Visual hallucinations have been described as a "film running through the head" or as a waking dream with strong emotional content. Images can be intrusive. More commonly they may involve seeing colored forms that shift in size and shape.

- Auditory hallucinations may include random sounds or elaborate melodies.

- A person may also hallucinate feelings of rubbing or light touches, even levitation.

Such symptoms may also appear in other sleep disorders and are probably related to extreme sleepiness. In general, cataplexy must also be present for a clear diagnosis of narcolepsy. It is possible, however, for some patients with narcolepsy to experience hypnagogic or hypnopompic hallucinations and daytime sleepiness and not cataplexy.

Microsleep and Automatic Behavior. In some cases, patients have so-called microsleep episodes, in which they behave automatically without conscious awareness. Such automatic behavior may not be recognized as part of a disorder by either patients or the people around them. Some examples include:

- People with narcolepsy can be driving or walking competently but end up in a location different from the intended one.

- A narcolepsy patient can be carrying on a conversation and jump from one unrelated topic to another or just trail off and stop talking altogether.

- The patient may suddenly perform bizarre actions, such as putting socks in the refrigerator.

- Patients may have severe forgetfulness.

- Their movements may suddenly become slow or clumsy.

- In some cases, their behavior may resemble some forms of epileptic seizures.

Disturbed Sleep. Nighttime sleep is often disturbed in narcolepsy, but it is usually mild to moderate and does not account for the daytime sleepiness experienced by people with narcolepsy.

Periodic Limb Movement Disorder. Many patients with narcolepsy experience periodic limb movement disorder, also called PLMD (formerly known as nocturnal myoclonus). In PLMD, the leg muscles involuntarily contract every 20 - 40 seconds during sleep, occasionally arousing the patient. The patient is usually unaware of the cause of the interruption.

Healthy Sleep

Most people need about 8 hours of sleep each day. Individual adults differ in the amount of sleep they need to feel well rested, however. (Infants may sleep as many as 16 hours a day.)

The daily cycle of life, which includes sleeping and waking, is called a circadian (meaning "about a day") rhythm, commonly referred to as the biological clock. Hundreds of bodily functions follow biologic clocks, but sleeping and waking comprise the most prominent circadian rhythm. The sleeping and waking cycle is about 24 hours. (If confined to windowless apartments, with no clocks or other time cues, sleeping and waking as their bodies dictate, humans typically live on slightly longer than 24-hour cycles.) It usually takes the following daily patterns:

- Humans function best with daytime activity and nighttime rest.

- Additionally, there is a natural peak in sleepiness at mid-day, the traditional siesta time.

Daily rhythms intermesh with other factors that may interfere or change individual patterns:

- The fraction-of-a-second-firing of nerve cells in the brain may be faster or slower in different individuals.

- The monthly menstrual cycle in women can shift the pattern.

- Light signals coming through the eyes reset the circadian cycles each day, so changes in season or various exposures to light and dark can unsettle the pattern. The importance of sunlight as a cue for circadian rhythms is shown by the problems people who are totally blind experience. They commonly have trouble sleeping, and experience other biorhythm disruptions.

Sleep Cycles

Sleep consists of two distinct states that alternate in cycles and reflect differing levels of brain nerve cell activity.

Non-Rapid Eye Movement Sleep (Non-REM). Non-REM sleep is also termed quiet sleep. Non-REM is further subdivided into three stages of progression:

- Stage 1 (light sleep)

- Stage 2 (so-called true sleep)

- Stage 3 to 4 (deep "slow-wave" or delta sleep)

With each descending stage, awakening becomes more difficult. It is not known what governs Non-REM sleep in the brain. A balance between certain hormones, particularly growth and stress hormones, may be important for deep sleep.

Rapid Eye-Movement Sleep (REM). REM sleep is termed active sleep. Most vivid dreams occur in REM sleep. REM-sleep brain activity is comparable to that in waking, but the muscles are totally relaxed, possibly preventing people from acting out their dreams. In fact, except for vital organs like lungs and heart, the only muscles not relaxed during REM are the eye muscles. REM sleep may be critical for learning and for day-to-day mood regulation. When people are sleep-deprived, their brains must work harder than when they are well rested.

The REM/Non-REM Cycle. The cycle between quiet (non-REM) and active (REM) sleep generally follows this pattern:

- After about 90 minutes of non-REM sleep, eyes move rapidly behind closed lids, signifying REM sleep.

- As sleep progresses the non-REM/REM cycle repeats.

- With each cycle, non-REM sleep becomes progressively lighter, and REM sleep becomes progressively longer, lasting from a few minutes early in sleep to perhaps an hour at the end of the sleep episode.

Causes

Genetic Factors

Narcolepsy has a genetic component and tends to run in families. An estimated 8 - 10% of people with narcolepsy have a close relative who has the disorder. An individual with a family member who has narcolepsy is 20 - 40 times more likely to have narcolepsy, compared to a person with no family history of the disease.

However, genetics are not the only factor involved in narcolepsy. Narcolepsy most likely involves a combination of genetics and one or more environmental triggers, such as infection, trauma, hormonal changes, immune system problems, or stress. Researchers are looking for specific genetic mutations that may make individuals susceptible to this disorder, and have discovered recently that most affected individuals carry the HLA DQB1(*)0602 gene. More recent studies also show that the TCR-alpha gene, which interacts with the HLA genes, is also involved in narcolepsy.

Autoimmunity

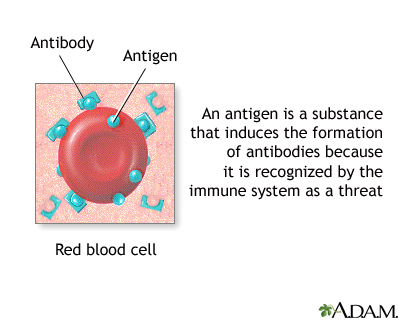

It has been theorized that narcolepsy may be an autoimmune disease, in which the immune system may be tricked into perceiving its own proteins to be antigens. (Antigens are foreign substances targeted for attack by immune factors in the body.)

Important autoimmune diseases include multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and type 1 diabetes. In such diseases, the immune system overproduces potent factors called cytokines, which cause inflammation and injury in the susceptible cells and tissues affected by the disease. Most autoimmune diseases also tend to afflict those with particular genetically determined molecules of the immune system called human leukocyte antigens (HLAs).

Some research suggests that an immune attack in narcolepsy may occur against cells containing the brain peptide hypocretin (orexin). Hypocretin deficiency is the major component of narcolepsy with cataplexy. Recent studies have shown a reduced amount of hypocretin-positive neurons in patients with narcolepsy with cataplexy. Hypocretin deficiencies might set off chemical responses that produce sleep attacks.

HLAs, particularly the above-mentioned subgroup known as (HLA)DQB1-0602, have been strongly associated with narcolepsy and low levels of hypocretin. Narcolepsy patients who carry this HLA group tend to have a specific collection of symptoms that include cataplexy and periodic limb movement disorder. However, roughly 20% of people without narcolepsy carry these HLA types.

Risk Factors

Narcolepsy affects about 1 in 2,000 people. Experts estimate that around 135,000 - 200,000 Americans have narcolepsy, but the number may be higher. Only about 25% of people who have narcolepsy are actually diagnosed with the disorder. Patients are often mistakenly diagnosed with other conditions, such as psychiatric or emotional problems. Many patients wait decades before receiving a proper diagnosis.

Age

Narcolepsy symptoms usually first appear in adolescence or young adulthood. However, narcolepsy can begin at any age. Growing evidence suggests that the disorder may emerge in early childhood in many patients. It can often be misdiagnosed as another disorder, such as ADHD or depression. People who develop it at a young age often have a family history of the disease and a severe condition, suggesting that genetic factors are important in this group.

Complications

Narcolepsy is a life-long problem, but it is not progressive. Symptoms may even lessen over time, but they never completely disappear. In older adults, cataplexy may lessen over time, but sleep disturbances at night may worsen.

Risk for Accidents

Perhaps the most serious consequence of narcolepsy is the high risk for accidents. In one survey, almost 75% of patients with narcolepsy reported falling asleep while driving, and 56% reported nearly having accidents. Other common narcolepsy-related accidents include burns from touching hot objects, cuts from sharp objects, and breaking things.

Effects on Mental Functioning

Some studies report that people with narcolepsy have problems with memory, thinking, and attention. Whether these problems are more likely to be due to tiredness and episodes of sleepiness than to brain abnormalities is not clear.

Emotional and Social Difficulties

People with narcolepsy suffer emotional and social difficulties caused by their uncontrollable sleep episodes and cataplexy. Studies have reported rates of depression in people with narcolepsy ranging from 30 - 57%. (In the general population, the prevalence of depression is 8%.) Studies have shown severe emotional and social dysfunction in all areas, including work, relationships, and leisure activities. Men with narcolepsy frequently suffer from sexual problems. Some experts believe that the psychological and social effects are more serious than those caused by epilepsy (for which narcolepsy can be mistaken).

Accompanying Physical Problems

Obesity. People with narcolepsy are at high risk for obesity compared to the general population. This could be a consequence of low activity level, but research also indicates that deficiencies in the brain peptide hypocretin may play a role in both narcolepsy and eating behaviors, which could increase the risk for obesity.

Diagnosis

Although narcolepsy is a physical disorder, doctors are still very likely to misdiagnose patients as having psychological problems. For most patients, narcolepsy is not diagnosed for up to 10 - 15 years after their symptoms first began. To determine specific sleep disorders, the doctor will take a medical and family history. The patient should tell the doctor about any medications the patient takes. The symptoms of narcolepsy are relatively easy to recognize if a patient reports all of the major symptoms:

- Excessive daytime sleepiness with a tendency for frequent naps. (These frequent naps should occur every day for at least 6 months to suggest the diagnosis of narcolepsy.) Narcolepsy is usually diagnosed in adolescence and young adulthood when falling asleep suddenly in school brings the problem to attention.

- Cataplexy.

- Hypnagogic hallucinations.

- Sleep paralysis.

Diagnosis based only on symptoms, however, is often problematic for various reasons:

- Patients often seek medical help for single symptoms (sleep paralysis or hypnagogic hallucinations) that might be associated with other disorders, particularly epilepsy.

- Symptoms are sometimes not dramatically apparent for years, even to the patient or a skilled observer. In some cases, the patient may need to consult a sleep specialist or go to an accredited sleep disorder center for accurate diagnosis of a sleep disorder. Patients should carefully investigate centers to make sure that they offer full sleep studies. Patients who visit a sleep center undergo an in-depth analysis, usually supervised by a multidisciplinary team of consultants who can provide both physical and psychiatric evaluations.

In the future, measurements of hypocretin-1 in the cerebrospinal fluid may prove valuable in identifying difficult to diagnose cases of narcolepsy, since hypocretin is often absent in patients with the condition.

Questionnaires

A doctor may administer certain questionnaires on sleeping habits, such as the Stanford Sleepiness Scale or the Epworth Sleepiness Scale.

The Epworth Sleepiness Scale. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) uses a simple questionnaire to measure excessive sleepiness and differentiate it from normal daytime sleepiness.

The Epworth Sleepiness Scale | |

Situation | Chance of Dozing 0 = no chance of dozing 1 = slight chance of dozing 2 = moderate chance of dozing 3 = high chance of dozing |

Sitting and reading | (Indicate a score of 0 - 3) |

Watching TV | (Indicate a score of 0 - 3) |

Sitting inactive in a public place (a theater or a meeting) | (Indicate a score of 0 - 3) |

As a passenger in a car for an hour without a break | (Indicate a score of 0 - 3) |

Lying down to rest in the afternoon when circumstances permit | (Indicate a score of 0 - 3) |

Sitting and talking to someone | (Indicate a score of 0 - 3) |

Sitting quietly after a lunch without alcohol | (Indicate a score of 0 - 3) |

In a car, while stopped for a few minutes in traffic | (Indicate a score of 0 - 3) |

Score Results | 1 - 6: Getting enough sleep 4 - 8: Tends to be sleepy but is average 9 - 15: Very sleepy and should seek medical advice Over 16: Dangerously sleepy |

Multiple Sleep Latency Test

The multiple sleep latency test (MSLT) uses a machine that measures the time it takes to fall asleep lying in a quiet room during the day. The patient takes 4 or 5 scheduled naps 2 hours apart. People with healthy sleep habits fall asleep in about 10 - 20 minutes. In patients with narcolepsy, polysomnography (see below) plus MSLT will show a much shorter duration of time (fewer than 8 minutes) from wakefulness into sleep. At least 2 of the naps are REM-onset (the active sleep phase associated dreaming). The test has limitations, however. There is no clear definition of exactly which abnormal results would indicate narcolepsy. It is most useful for measuring the severity of the problem. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale may be more accurate in differentiating narcolepsy from normal daytime sleepiness.

Polysomnography

An overnight sleep study, called polysomnography, can be a valuable means for determining the basic cause of sleepiness. The patient arrives at the sleep center about 2 hours before bedtime without having made any changes in daily habits. The patient will be monitored by a variety of devices while sleeping:

- Electroencephalogram, or EEG (monitors the electrical activity of the brain)

- Electrocardiogram or ECG (monitors the heart)

- Electromyogram (monitors the movements of muscles)

- Electrooculogram (monitors eye movements)

These instruments record activity as the patient passes, or fails to pass, through the various sleep stages.

Ruling out Other Disorders

Ruling out Other Sleep Disorders. Other sleep disorders can share some or all of the symptoms of narcolepsy:

- Patients with obstructive sleep apnea also experience sleep disturbance and excessive daytime fatigue. (A

person may have both sleep apnea and narcolepsy.) - Idiopathic hypersomnia is a less well-defined syndrome in which patients have excessive daytime sleepiness without evidence of cataplexy. Patients have a hard time becoming fully awake despite an adequate amount of sleep.

- Chronic sleep deprivation

- Secondary narcolepsy, resulting from head trauma, tumors, vascular malformations in the brain, multiple sclerosis, or Parkinson's disease

Ruling out Psychological Disorders. In one study, 40% of patients who actually had narcolepsy had been diagnosed incorrectly with some psychological or psychiatric problem. Certainly, patients with narcolepsy have emotional difficulties because of the condition, and it is often difficult, particularly for a nonspecialist, to detect the physical problem. Even worse, hypnagogic hallucinations may result in diagnoses of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, which are treated with potent antipsychotic drugs that have severe side effects and are useless for narcolepsy.

Ruling out Epilepsy. Narcolepsy can easily be mistaken for epilepsy, a group of disorders that cause seizures. Case studies have reported a misdiagnosis of epilepsy in patients who were actually experiencing cataplexy and sleep paralysis.

Other Causes of Persistent Fatigue. A number of conditions can cause persistent fatigue and should be ruled out, including chronic fatigue syndrome.

These conditions may also worsen sleep paralysis in narcolepsy. Narcolepsy sleep paralysis usually occurs at the onset of sleep and is chronic.

Treatment

Lifestyle treatment of narcolepsy includes taking three or more scheduled naps throughout the day. Patients should also avoid heavy meals and alcohol, which can interfere with sleep.

People with mild narcolepsy symptoms who do not need medication may be able to maintain alertness with sleep scheduling. The role of scheduled naps for patients who are responding to medications for narcolepsy remains unclear.

Medications for narcolepsy target the major symptoms of sleepiness and cataplexy. Stimulant drugs are used to manage excessive daytime sleepiness while antidepressants and other compounds address cataplectic symptoms. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved three drugs specifically for the treatment of narcolepsy. They are now the first-line treatments:

- Modafinil (Provigil): For excessive, uncontrollable, daytime sleepiness

- Armodafinil (Nuvigil)

- Sodium oxybate (Xyrem): For cataplexy and excessive daytime sleepiness

Drug Treatments for Sleepiness

Modafinil. Modafinil (Provigil) is a drug used to treat the excessive sleepiness associated with narcolepsy and other sleep disorders. It has largely replaced methylphenidate (Ritalin) and other stimulants for treatment of narcolepsy sleepiness. Patients who switch to modafinil from stimulants such as methylphenidate have few problems if they gradually taper off the stimulant dose.

Modafinil helps patients with narcolepsy stay awake during the day. While only some experience normal wake times, patients taking modafinil often have up to a 50% improvement in the ability to stay awake, as well as a 25% reduction in the number of involuntary sleep episodes. It has not been proven to be safe in pregnant women. Pregnant women or those wishing to get pregnant should discuss the risks and benefits of this medication with their doctors.

Some of modafinil's additional benefits include what it does not do:

- Modafinil does not appear to affect natural hormones important in sleep, including cortisol (the major stress hormone), melatonin, and growth hormone. Therefore, studies suggest that it does not interfere with voluntary naps during the day or with the quantity or quality of nighttime sleep.

- It does not cause anxiety to the degree that the standard stimulants do.

- It does not cause a rebound effect as stimulants do. In other words, people who take modafinil do not usually "crash" when the drug wears off.

- It has less potential for abuse than stimulant drugs. However, modafinil can still be habit-forming. Patients may need to gradually lower the dose before stopping treatment.

Side effects of modafinil may include:

- Headache (the most commonly reported side effect)

- Nausea

- Diarrhea

- Dry mouth

- Nasal and throat congestion

- Nervousness and anxiety

- Dizziness

- Back pain

- Difficulty sleeping

- Decreases in the effects of hormonal methods of birth control, including the pill. (Women of childbearing age who take modafinil should switch to another form of birth control.)

- Modafinil is approved only for adults and should not be given to children.

Armodafinil (Nuvigil) is a newer drug, which is nearly identical to modafinil. In clinical trials comparing it with placebo, armodafinil improved wakefulness, memory, attention, and fatigue in patients with narcolepsy.

Drug Warning

In October 2007, the FDA added new safety information to the prescribing label of modafinil (Provigil) and armodafinil (Nuvigil). The new information warns that:

- Rare but serious skin reactions, such as Stevens-Johnson Syndrome, have been reported with modafinil and armodafinil use. Patients should stop taking these medications at the first signs of any rash, and immediately contact their doctors.

- Psychiatric side effects, such as anxiety, mania, hallucinations, and suicidal thinking, have been reported. Doctors should be cautious about prescribing modafinil and armodafinil to patients with a history of psychosis, depression, or mania.

Stimulants. Medications that act as stimulants are standard treatments for narcolepsy. They include:

- Methylphenidate (Ritalin)

- Dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine)

- Methamphetamine (Desoxyn)

Methylphenidate and dextroamphetamine last for 2 - 5 hours and used to be the standard drugs for excessive daytime sleepiness. These drugs are useful for people who can manage wakefulness with a night's sleep and scheduled naps. They can improve mood, mental acuity, and other aspects of mental functioning. However, the evidence to support their benefit for patients with narcolepsy is not a strong as with modafinil.

Stimulants can have unpleasant side effects, including:

- Weight loss

- Dizziness

- Nausea

- Changes in blood pressure and rapid heartbeat

- Headache

People with heart disease, hyperthyroidism, glaucoma, anxiety disorder, and high blood pressure should avoid stimulants, or take them only with a doctor's supervision.

These drugs become ineffective if used continuously, and patients are advised to take a drug holiday one day a week or to withdraw gradually and resume treatment at a lower dose. Patients should not engage in activities that require being awake (such as driving) during withdrawal.

Drug Treatments for Cataplexy

Sodium oxybate (Xyrem). Sodium oxybate (Xyrem), also referred to as gamma hydroxybutyrate (GHB), helps reduce the frequency of cataplexy attacks and improve daytime sleepiness. Patients need to take GHB for about 4 weeks before they notice significant benefits. It may take an additional 4 weeks for the drug to reach maximum effect. Food intake can affect the actions of GHB, so patients are advised to take it at a regular time after the evening meal.

The FDA has placed tight restrictions on the use of this drug. Although the drug appears to be effective and safe when used for narcolepsy, it has a history of illegal and "date-rape" use, with street names such as "Grievous Bodily Harm" or "Liquid Ecstasy." (Despite this name, GHB is not the same as "Ecstasy," a street drug with different effects.) In high doses, GHB can cause dependence over time. Education through the Xyrem Success Program may be valuable to patients and physicians.

Very serious side effects -- including seizures, coma, respiratory arrest, and death -- have been reported in people who abused GHB. Trials of Xyrem, however, have not reported these effects with the doses used in treatment for cataplexy.

Antidepressants. Antidepressant drugs are not approved for treatment of cataplexy, but they are commonly used to manage this condition. Unfortunately, there have been few studies conducted on antidepressant treatment of cataplexy, and there are little data on which type of antidepressant work bests.

Antidepressants used for cataplexy, hallucinations, sleep paralysis, and management of REM symptoms include:

- Tricyclic antidepressants: Protriptyline (Vivactil), clomipramine (Anafranil), imipramine (Janimine, Tofranil), and desipramine (Norpramin, Pertofrane)

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): Fluoxetine (Prozac), paroxetine (Paxil), and sertraline (Zoloft)

- Newer antidepressants: Venlafaxine (Effexor)

Tricyclics were the first antidepressants used for cataplexy; they were also one of the first treatments for cataplexy. They can be helpful for some patients but have many unpleasant side effects, including dry mouth, constipation, and weight gain. Tricyclics can also lower blood pressure and cause disturbances in heart rhythm.

SSRIs have fewer side effects than tricyclics but may not work as well for cataplexy control. The most common side effects include nausea, drowsiness or insomnia, headache, weight gain, and sexual dysfunction.

Venlafaxine (Effexor) is a selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SSNRI) that has shown promising results for treatment of cataplexy. Some patients with narcolepsy, and their doctors, report that venlafaxine seems to work best of all the antidepressants.

Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs). Selegiline (Eldepryl, Movergan), also known as deprenyl, is an MAOI that blocks monoamine oxidase B, an enzyme that degrades dopamine. MAOIs may play a role in narcolepsy, but how much benefit this group of drugs provides is not well proven.

Selegiline has significant side effects:

- It interacts with nearly every antidepressant. Patients suffering from depression should discuss all treatment options with their doctor.

- People taking any monoamine oxidase inhibitor are at risk for high blood pressure if they consume tyramine-containing foods or beverages, including aged cheeses, most red wines, vermouth, dried meats and fish, canned figs, fava beans, and concentrated yeast products.

Resources

- www.aasmnet.org -- American Academy of Sleep Medicine

- www.sleepfoundation.org -- National Sleep Foundation

- www.narcolepsynetwork.org -- Narcolepsy Network

- www.med.stanford.edu/school/psychiatry/narcolepsy -- Stanford Center For Narcolepsy

- www.nhlbi.nih.gov/sleep -- National Center on Sleep Disorders Research

- www.ninds.nih.gov -- National Institute on Neurological Disorders and Stroke

References

Ahmed I, Thorpy M. Clinical Features, Diagnosis and Treatment of Narcolepsy. Clin Chest Med. 2010;31:371-381.

Cao M. Advances in Narcolepsy. Med Clin N Am. 2010;94:541-555.

Cochen De Cock V, Dauvilliers Y. Current and future therapeutic approaches in narcolepsy. Future Neurol. 2011;6(6):771–782.

Dodel R, Peter H, Spottke A, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with narcolepsy. Sleep Med. 2007 Nov;8(7-8):733-41. Epub 2007 May 18.

Hayes, D. Narcolepsy. In: Ferri FF, ed. Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2013. 1st ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Mosby Elsevier; 2012.

Hallmayer J, Faraco J, Lin L, Hesselson S, et al. Narcolepsy is strongly associated with the T-cell receptor alpha locus. Nat Genet. 2009;41(6):708-711.

Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Xyrem Prescribing Information. Available online.

Luc ME, Gupta A, Birnberg JM, Reddick D, Kohrman MH. Characterization of symptoms of sleep disorders in children with headache. Pediatr Neurol. 2006;34(1):7-12.

Mahowald, M. Disorders of sleep: Specific Sleep Disorders. In: Goldman L, Ausiello D, eds. Cecil Medicine. 23rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:chap 429.

Morgenthaler TI, Kapur VK, Brown T, Swick TJ, Alessi C, Aurora RN, et al. Practice parameters for the treatment of narcolepsy and other hypersomnias of central origin. Sleep. 2007 Dec 1;30(12):1705-11.

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. NINDS Narcolepsy Information Page. Available online.

Owens, J. Sleep medicine. In: Kliegman: Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 19th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2011:chap 17.

Pagel JF. Excessive daytime sleepiness. American Family Physician. 2009;79(5).

Thorpy MJ. Cataplexy associated with narcolepsy: epidemiology, pathophysiology and management. CNS Drugs. 2006;20(1):43-50.

Vignatelli L, Alessandro R, Candelise L. Antidepressant drugs for narcolepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD003724.

|

Review Date:

9/29/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M. Health Solutions, Ebix, Inc. |